By Zach Carter and Trey Gilbert

In 1978, Jen Field was a fourth grader in Angola, Ind. During her gym class, the boys were allowed to do pull-ups while Jen was forced to do arm hangs. Irritated, she held on for 90 seconds and broke the school time record. Why was she not allowed to do pull-ups? The answer: she was a girl.

On Oct. 29, 2021, her daughter, Nicki Southerland, was walking down the Learning Stairs at the end of the school day. There was something different about this walk. The Delta High School band performed for the sophomore cross country runner and the entire student body gave her a sendoff as she left for the IHSAA State Championships. She placed state runner-up the next day.

So why 43 years later is there such a difference in the attitudes toward girls in sports? In part because of the impact of a federal law called Title IX, which was passed in 1972 and is celebrating its 50th anniversary this year.

Before 1972, things like sports for high school girls were very different. While the boys got to represent the school on the field, girls often had to watch from the sidelines.

Nicki Southerland’s grandma, Bev Southerland, remembers what it was like in high school when she began as a freshman at Yorktown High School in 1962.

“I didn’t really think about playing a sport,” she says. “There was nothing available besides being in the pep club or being a cheerleader. That was about it for girls. They had something called Future Homemakers of America which told you how to basically be a wife and a mother.”

High school girls were required to take a home economics class in which they learned how to cook, clean and do other tasks that wives were “supposed” to do.

Even though Nicki’s grandmother never got the chance to participate in school sports, she attended many basketball and baseball games for the Yorktown Tigers. This is something she has continued with her children and grandchildren.

“I am very thankful that all my kids and grandkids got into sports because it is wonderful entertainment and it keeps them out of trouble,” she says.

Fifty years ago, Delta High School was like most high schools at the time. In 1971, there were seven boys’ sports varsity teams. The only girls’ team other than cheerleading was an intramural basketball team.

On June 23, 1972, a decision was made that would alter high school athletics for the next 50 years. The passing of federal Title IX legislation, authored by Sen. Birch Bayh of Indiana, would open the doors for girls and women to participate in the same activities as their male counterparts.

The official language for Title IX is as follows: No person in the United States shall, on the basis of sex, be excluded from participation in, be denied the benefits of, or be subjected to discrimination under any education program or activity receiving federal financial assistance.

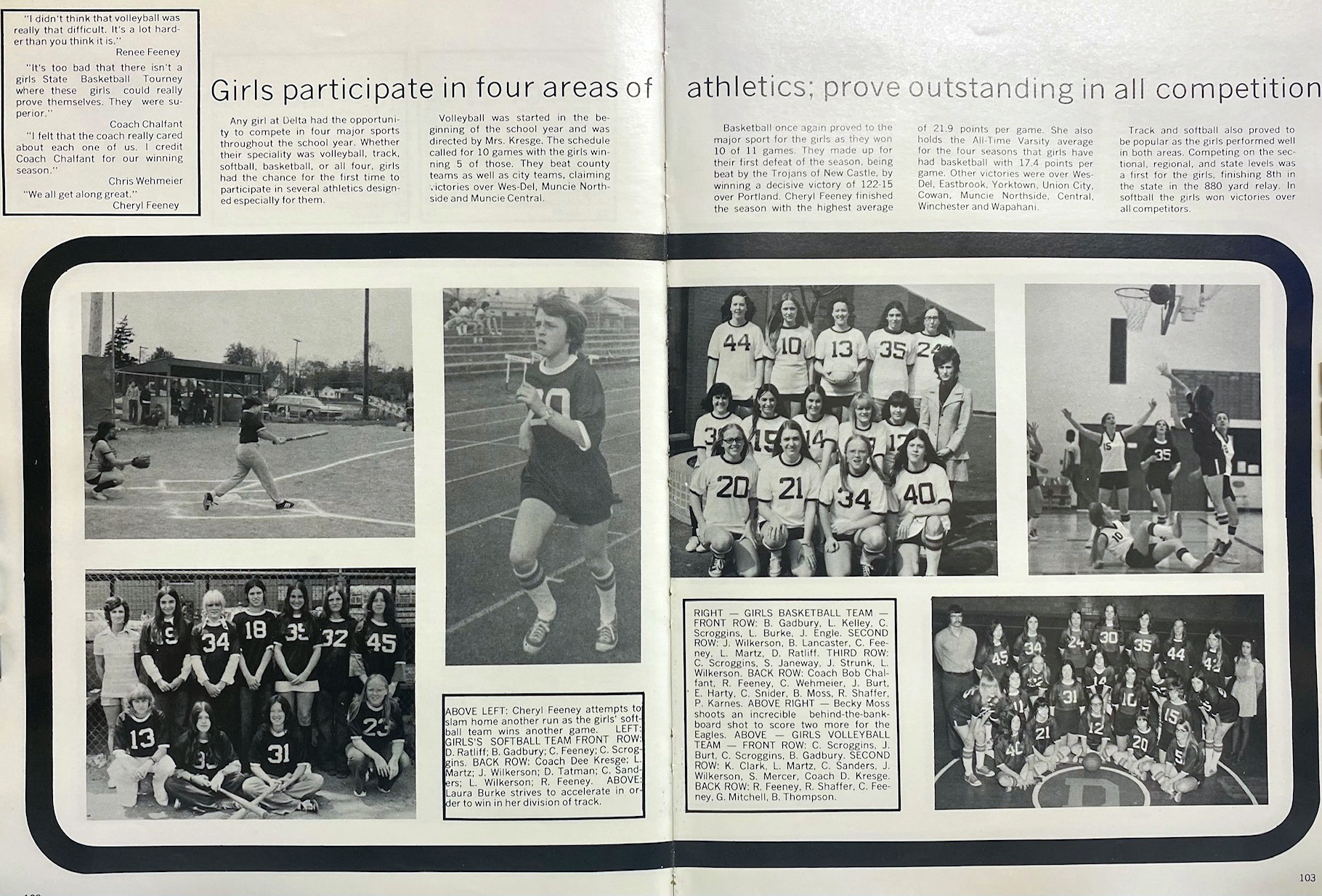

The school year after Title IX was passed is when things started to change at Delta High School. Girls that year were given the option to participate in four interscholastic sports: volleyball, track, softball, and basketball. But, just because Title IX was passed in 1972, does not mean everything changed right away.

Flash forward to 11 years later when Nicki’s mother, Jen, started high school in 1983. When she was in elementary school, girls were told if they ran too far, they would put themselves in physical danger. She remembers a famous incident where Katherine Switzer was tackled while running in the 1967 Boston Marathon — simply because she was a female.

In 1973, the Indiana High School Athletic Association started having girls’ events at the State Track meet. So when Nicki’s mother started high school in 1983, she wanted to run.

“As soon as I had the chance, I knew I wanted to run in every 5k race around the area because I could,” she says. “There were no girls’ running shoes or running shorts yet, so I wore the boys’ equipment. When running cross country as a freshman in 1983, there were few girls running, so sometimes we would just run in the boys’ race.”

During that year, she did not have any girl teammates. Despite that, she qualified for state. By her senior year, there were enough girls for a full girls’ team. Because of this, the girls decided how they wanted to act.

“I think since we were just gaining opportunities in sports that our mothers did not have, we had to be cautious about how we presented ourselves,” she says. “We should NEVER complain. We should not expect a modified workout. I never used weather or anything else as an excuse for underperforming. I never wanted to show any kind of weakness during a race. Girls should never cry and if we fell, we had to get back up and keep going. We felt an obligation to show that we were as tough as the boys, if not tougher, so that others would think we deserved our chance to compete.”

With this attitude, the team would go on to qualify for state. After high school, Nicki’s mother would go on to run at the University of Indianapolis.

“In 1987, I was recruited to run by UIndy, and that was when the effects of Title IX really gained momentum, as so many universities now had women’s sports,” she says. “There were partial scholarships for women in nearly every sport by then.”

Today, Nicki Southerland already has the attention of college recruiters as one of the nation’s top young runners. The cross country, track and swimming athlete appreciates what Title IX has done for herself and all high school girls over the past 50 years. She also appreciates the way Delta has made her feel.

“I have gotten a lot of support from Delta,” Nicki says. “‘It is just amazing because of the community and they have really given me a lot of opportunity.”

The Southerland family is an example of how Title IX has changed female athletes’ lives over the years. But there is much more that went on behind the scenes.

In addition to athletics, Title IX also brought equality to the classroom, ensuring everyone is given the same opportunities to take what class they want regardless of gender.

But with great change to a long held system there is always pushback from people refusing to change and some oversights that linger.

So because of this, Title IX is regulated by school administrators. As far as athletics, if school administrators learn of any misconduct that they need help or information on, they reach out to the IHSAA. They are the governing body when it comes to high school sports in Indiana.

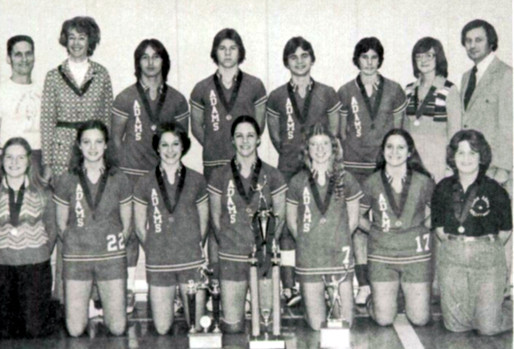

An example of the IHSAA doing a ruling connected to Title IX is the case in 1976 when a girls’ volleyball team from South Bend Adams High School won the state championship with three boys on the roster. This happened because the earliest interpretations of the Title IX law did not prevent boys from being on girls’ teams. In fact, a boy had played volleyball for state runner-up South Bend Clay the previous season.

These boys were playing on the girls’ teams because their schools did not offer boys’ volleyball teams — and Title IX promoted equal opportunities regardless of gender.

But two days after this controversial 1976 championship, the IHSAA amended its rules and decided that boys no longer would be allowed to play on girls’ sports teams.

Current IHSAA assistant commissioner Mrs. Sandra Walter talks about that situation and why the decision was made.

“The level playing field was disrupted,” she says. “That’s when you saw (a new rule) come in to play for us at the IHSAA and that boys may not compete on a girls’ team. There is not a level playing field when you have different genders at that age.”

Since this rule has been made, there has been debate about allowing boys on volleyball teams. But recently, boys’ volleyball may be a sport that is gaining traction just like girls’ wrestling. Neither is an official IHSAA-sanctioned sport yet, but both could be soon.

“We have always had a bylaw where if the 407 schools within Indiana now reach a percentage threshold (of schools offering a specific sport), we would start to offer a sport that is supported by a high percentage at our schools,” Walter says. “We are implementing as emerging sports boys’ volleyball and girls’ wrestling. There has been a lot of chatter about that lately.”

Another hot topic currently in high school sports is transgender inclusion. Walter discusses how the IHSAA is working on that.

The IHSAA passed a gender policy in 2017. This policy outlines what transgender students must do if they want to participate in a sport in the gender in which they identify. First, they must prove they have been living that identity for at least one year. And second, transgender students who identify as girls must have undergone surgery or hormone therapy for at least one year.

“We try to take care of our transgender athletes and be mindful of the needs of every student,” she says. “It goes back to my first comment about inclusion and taking care of every kid every day. Our offices need to be mindful of that, too, and the transgender topic is certainly top of the mind for many right now.”

Recently, House Bill 1041 was passed in Indiana’s House of Representatives and is now with the Senate. The issue that has Hoosiers divided is what this bill states. The law would mean that whatever gender you are born, that is the sport gender you can play.

Even though Title IX has done a lot for high school sports, it also covers other elements. Topics such as hazing, sexual harassment, bullying and pregnant or married students are also included in the Title IX legislation. All of the topics related to Title IX are reviewed by a Title IX director. Each school corporation in Indiana must have a Title IX administrator. At Delta, this is assistant superintendent Dr. Darin Gullion.

“The courts have consistently ruled that Title IX includes gender identity and the U.S. Department of Education has made clear that gender identity is part of the defintition of sex under Title IX discrimination protections,” Dr. Gullion said.

Athletic director Tilmon Clark said he works to make sure he treats boys and girls equally in all areas.

“I go to a girls’ basketball game and a boys’ basketball game. I want to see both of them succeed and have the same opportunities to showcase their talents,” he said. “It’s incredible to see when female athletes succeed just like male athletes when they have those opportunities.”

In conclusion, Title IX has revolutionized the way girls are treated not just in sports but in their entire academic studies.

But in the coming years, it appears the equality debate may shift more toward gender identity.

“I would love to say that in the next 50 years, we will treat an athlete like an athlete, a student like a student, and that approach is taken from everyone involved within the educational world,” Walter says.